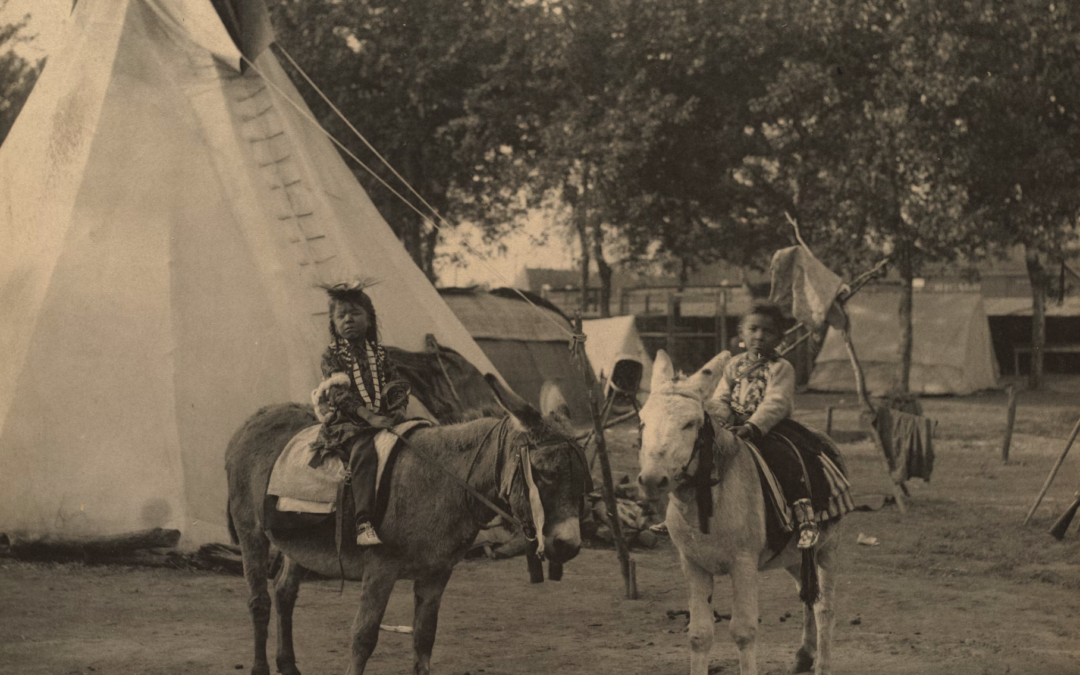

Image credit: The Boston Public Library via Unsplash

I recently read a book called As Long As Grass Grows by Dina Gilio-Whitaker. In the book, she sets out to help her readers gain a deeper understanding of the various forms of environmental injustice and Indigenous injustice. She highlights how settler colonialism and environmental deprivation play a significant role in contributing to Indigenous and environmental injustice while emphasizing the ways we, as a society, can repair this and bring about environmental justice.

Throughout the history of the United States, Indigenous peoples have encountered genocide, forced assimilation, cultural erasure, displacement, environmental deprivation, starvation, land dispossession, and much more. Environmental justice must take this into account in order to comprehensively right the wrongs done to Indigenous communities. Gilio-Whitaker states that we ought to think of reforming environmental justice as a “project to ‘Indigenize’” (Gilio-Whitaker, 2019, 38). By shifting the focus to center on environmental issues faced by Indigenous communities, we can begin to decolonize environmental justice methods and frameworks. The environmental justice movement must effectively dismantle the deep-rooted mechanisms of neoliberalism, capitalism, the patriarchy, and manifest destiny. These cultural beliefs and policies are the root causes of environmental injustice and, thus must be fully dismantled from environmental justice frameworks.

The basic concept of Indigenous peoplehood is that their identity is developed alongside the natural world. Indigenous communities believe they have a sense of duty towards their local flora and fauna as well as their surrounding natural environment as a whole. Indigenous culture and lifeways are derived from their land. Their language, ceremonies and religious practices, traditional food sources, and historical knowledge are deeply rooted in their natural environment (Gilio-Whitaker, 2019, 83). Environmental justice centered around a European viewpoint denies the spiritual and cultural existences evident in Indigenous civilizations.

Colonialism exploits the native population for its own advantage, whereas the fundamental goal of settler colonialism is the erasure of the other. Gilio-Whitaker views settler colonialism as not merely a historical affair but as a structure designed to eradicate the Native population through any means necessary in order to achieve land. Environmental deprivation, in regard to Indigenous peoples and settler colonialism, refers to the strategic historical methods of land and resource dispossession designed to ensure the eradication of Indigenous peoples and their cultures.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker emphasizes that in order to truly make strides toward a more inclusive and just environmental justice movement, we must indigenize it. We must transform it to account for the complex and intricate histories, cultures, and relationships of the Native peoples. Gilio-Whitaker asserts that “…for this process to be effective it must confront both the foundation of white supremacy that inflects the social and legal landscape of the US and the ways white supremacy continues to obstruct those relationships” (Gilio-Whitaker, 2019, 239). While the environmental justice movement has been working to amplify Indigenous voices and help to get Indigenous rights recognized in a political and societal manner, Indigenous rights are being attacked in new ways. We must account for these attacks by dismantling western environmentalism, stereotypes and misinformation, the notion of manifest destiny, capitalism, neoliberalism, the patriarchy, and any other historical and out-of-date belief woven into the foundations of environmentalism. It is imperative that we make it a point to critique the effects in our society and confront their roots in environmental justice.