When I was growing up, the family lore was that my dad’s grandmother was Cherokee. He grew up in High Point, NC. He lived in Michigan when I was young, and after my parents divorced, I would visit him during the Christmas and summer holidays. I have vivid memories of driving down from Michigan to North Carolina and passing through Cherokee, North Carolina, on the reservation of the eastern band of Cherokee, and watching “Unto These Hills.” A play that “tells the triumphant story of the formation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians from first contact with Europeans through the years following the infamous Trail of Tears.” I remember shopping at the reservation gift shop in the late 70s, buying moccasins, and taking a picture with the elder Indian by the side of the road with the feather headdress.

I also remember feeling glad that I was at least part Cherokee because I didn’t want to identify with people who would inflict the Trail of Tears on innocent people. I liked thinking that there was a part of my DNA that was connected to the people in the play and to the Earth and the animals in the Great Smoky Mountains.

As November begins and we celebrate Native American Heritage Month, I wanted to reflect on the world in which I grew up, how different the world is today, and how we all can make the world better – and yes, how it relates to Native American Heritage Month.

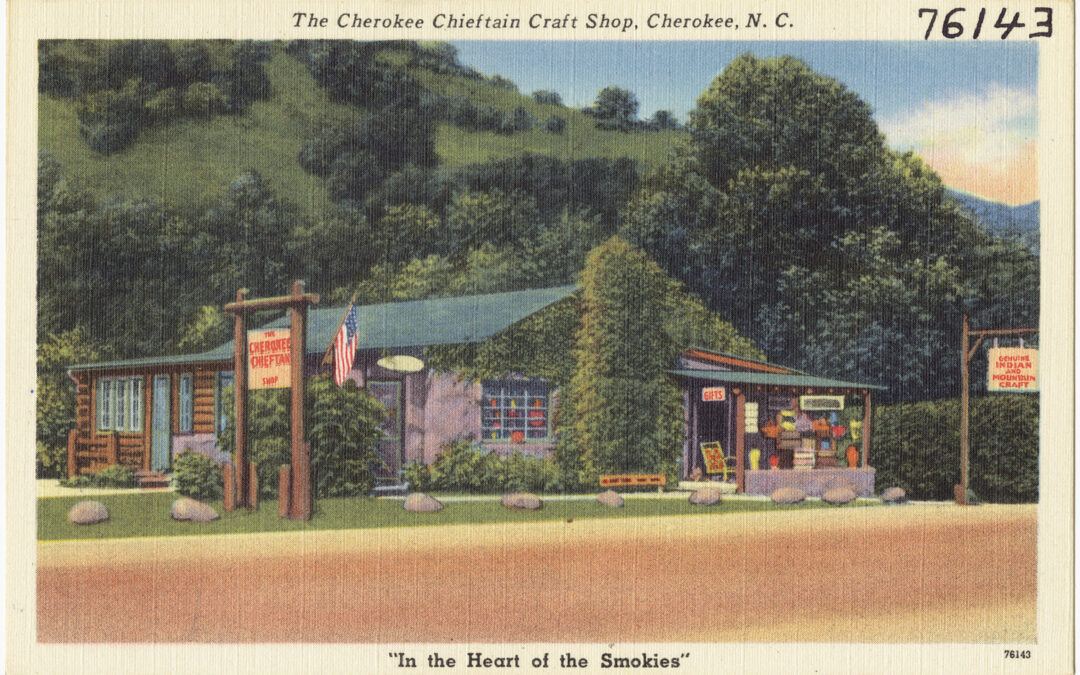

A few Christmases ago, I gave my dad a gift – a DNA test for him to swab his cheek and submit. We gave them to my parents and my in-laws just for fun. It turns out that my dad didn’t have any Cherokee DNA after all. I think somehow I felt like that genetic connection helped me identify more closely with the values and worldview of Indigenous people, and I didn’t have that now. I also didn’t know during our trips to North Carolina that the Cherokee elder standing by the teepee at the side of the road to take pictures with tourists wasn’t even dressed as a Cherokee. He was dressed to reflect what tourists wanted to see from the movies in which copyboys battled Indians on the Great Plains. This wasn’t the joyful cross-cultural experience I imagined it to be when I was 6 or 7. It was instead an experience rooted in exploitation.

As a society, we are in an incredibly powerful and unsettling time when what many of us used to believe about the world was wrong, but we don’t know exactly how to make it right. My teenage daughter and I recently watched some 80s movies from my Gen X youth. “Coming to America,” “Sixteen Candles,” “Adventures in Babysitting”… I am surprised that my friends and I didn’t notice back then – it was just the fishbowl we were swimming in. Oh, don’t get me wrong, I’m sure that those impacted by systemic racism were very aware of it, but it wasn’t part of the social conversation back then.

It is also clear that the removal of tribes from their territory in the US, slavery, colonialism, and, more recently, top-down approaches to development and conservation all emerged from a deeper power dynamic that is very difficult to dismantle. Most people can see that the old way is dying, but nobody is clear about what systems will replace it. In this shift to a new way of relating to others and sharing power, there are violent clashes between the old ways of separation and a new path of connection. There is no doubt that this is a confusing and scary time for many. It is important to remember that these old systems of power and control were always there; they are just more visible now. Even though it seems like it might be getting worse, it is just a necessary step to knowing and doing better.

In my conservation work over the years, I have seen many examples of communities that still practice some of their traditional ways of relating to communities, animals, and the land and water. I have seen an incredibly powerful and overdue movement to acknowledge indigenous wisdom and elevate it in conservation. I have heard questions about balancing traditional knowledge with conservation science knowledge and even if conservation science is still relevant. I’ve also seen a backlash of confusion, anger, refusal to see or acknowledge that anything was wrong with the old power balance, and a violent and extreme reaction to the conversation of equity. The pendulum is swinging away from old power holders to favor indigenous knowledge and wisdom, to level the playing field, and to bring new voices into the conversations about what matters. We can all celebrate that! No one has it figured out yet, so if we expand the conversation, we will have a better chance of bringing all types of wisdom to the table to figure out what replaces the old, dead system in as graceful and inclusive a way as possible.

Still, I sometimes wonder, what can I contribute to the new world we are all making together? I’m not Native American. I don’t have family stories of connections with animals like buffalo, salmon, or caribou. There is so much to learn from indigenous people around the world and from the tribes who are indigenous to these lands. We can do that in November during Native American Heritage Month, but it can’t stop when November ends.

Even though I don’t have a physical connection to the Cherokee, I know that the entire human race has evolved with animals, living with the land, and we are intricately connected. We may not be consciously aware of this connection in our everyday lives, but one out of every three bites of food comes from plants pollinated by bees, birds, bats, etc. We are dependent on nature for the air we breathe and the water we drink. And our souls are connected to every other being on the planet. I feel called to understand and amplify connections with nature from communities around the world, to bring what I have learned about wellbeing to communities that steward wildlife and support them in ways that are valuable to them through our Wild Happiness approach, and to communicate the value of that connection to anyone who wants to hear it. That’s why I started OneNature.

I want to continually expand my work and my life to be more inclusive. I had the pleasure of organizing a panel about ancestral connection to wildlife. I felt my world shift in real time as I heard the stories and deeply rooted worldview of connection described in the accounts from India, Zimbabwe, and the US Great Plains. I have participated in a beautiful collaborative research paper with ten conservation colleagues and local community representatives from all around the world. Every interaction teaches me something new and expands my own worldview of connection.

What are you called to do? Can you find a way to connect with nature in your own life? Can you open your hearts and minds and expand your worldview even more? Can you find ways to connect with other people, even if they are from a different place, religion, or group? When you do, you will be showing the way to a new world of connection. I’m happy to be on this journey with you.

Postcard: The Cherokee Chieftain Craft Shop, Cherokee, N. C., “In the heart of the Smokies” via the Boston Public Library.

Join our Newsletter Donate to bring Wild Happiness to communities and wildlife Follow us on socials!